0. Introduction

On January 21st, 2009, the day after US President Barack Obama took office, he signed a memorandum on “Transparency and Open Government.” The memorandum stressed that the government should be transparent, embrace citizen participation, and facilitate public-private collaboration to regain people’s trust in government. It not only reveals civil society’s strong desire for government transparency, openness, and participation, but indicates that open government is a new model of governance. From Occupy Wall Street to the Arab Spring, from Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement to Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution, the ideas of transparency and openness have become the driving force behind the wave of democratization movements of the 21st century.

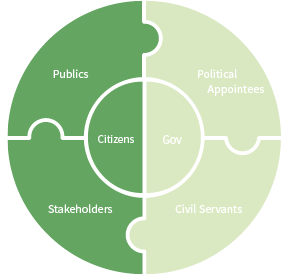

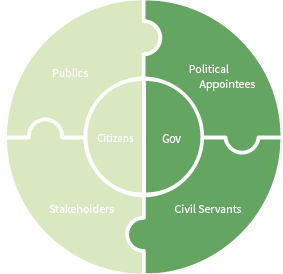

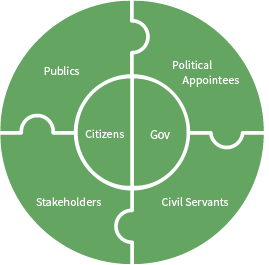

What is open government? The 2009 Presidential Memorandum stressed that transparency, participation, and collaboration are the keys to open government. In 2011, eight countries (Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, the Philippines, South Africa, the UK, and the US) launched the Open Government Partnership (OGP), which is committed to promoting transparency, participation, accountability, and inclusion. Open government is not just a slogan of reform but a political movement. It redefines the relationship between government and civil society and connects government, NPOs, international society, and individual citizens to form a network of stakeholders so as to break bureaucratic hierarchy and facilitate open governance.

Taiwan is not sitting out this global wave of open government. Many civil society organizations in Taiwan have long been advocating open data, citizen participation, and public-private collaboration. However, not until the 2014 Sunflower Movement was these topics discussed together in the context of open government. The Sunflower Movement stormed Taiwan and raised citizens’ awareness of government transparency and openness. After the movement, the government started to advocate open data and improve citizen participation as a response to the criticism from civil society. Therefore, when President Tsai Ing-wen took office in 2016, she spoke publicly for open government and appointed the first Digital Minister in Taiwan who is dedicated to open government. Despite these efforts, we found that open government has made little progress in the past three years due to lack of relevant laws and the culture of openness have not yet been established. Moreover, the Taiwanese Government did not have a clear blueprint of open government policies and most officials showed little political will to encourage relevant actions. This was especially true when it came to major national policies (such as the Infrastructure Development Program [1]). People have not been able to see the government as a system of transparency, participation, or collaboration in these policies, rendering open government an empty slogan of openwashing.

OPENWASHING:

This term is used to describe the situation in which a government pretends to be "open" with pretty slogans or superficial work while, in practice, does not take views from civil society into consideration. Openwashing turns "open" and "participation" into mere propaganda for government and something that has no tangible impact. As a result, civil society comes to have very limited imagination of what open government means.

In Taiwan, open government is relatively young and is still developing. As part of the democratization movement, open government cannot be achieved with mere slogans or empty promises. Taiwan is in urgent need of legal and organizational reforms, digital skill training for civil servants, and a new, open culture in civil society. This cannot be done by a few advocates. Open government is a duty not solely borne by the government but by every citizen as well. Only when the value of openness truly takes root in people’s mind will the mission of the movement be accomplished.

Taiwan Open Government Report examines the development of open government in Taiwan from 2014 to 2016. The report gives an introduction to the current situation and points out potential challenges. The purpose of this report is to provide a preliminary analysis and a basis for dialogue so that the public can understand the issues at stake. Moreover, advocates and policy makers can build on this report to make deeper analyses, critiques, and policy suggestions.

The body of this report consists of four chapters. It begins with a review of open government laws and policies and points out the problems in the current legal framework. We then use “transparency, participation, and collaboration” from the Presidential Memorandum as the structure of the other three chapters. Chapter Two uses the method of the Open Data Barometer to look into the readiness, implementation, and impact of open data in Taiwan. Chapter Three analyzes the development of citizen participation through several case studies. Chapter Four explores civic tech collaboration between civic tech communities and the government. We want to stress that these four chapters are not the full picture of open government in Taiwan but research directions selected by the researchers after significance and feasibility evaluation. While this report may not cover all important issues, it is expected to serve as a building block of more advanced research and analysis.

Taiwan Open Government Report is a research project conducted by the Open Culture Foundation (OCF). The OCF was established in 2014 with the support of multiple open source communities in Taiwan. Its mission is to promote open source, open data, and open government. OCF researchers, Lee Mei-chun and Tseng Po-yu, collected the materials, wrote, and edited this report. During the research, civic tech communities were invited to collaborate in hackathons and workshops. The drafts were also open to public comments. This report could not be possible without the help of many dedicated members from the g0v community, the open data community, and the government. We appreciate all the comments and critiques. This report is published in both Chinese and English, inviting both domestic and international readers to learn about Taiwan’s experiences. We would also like to invite readers to interact with us and play with the data on the report’s official website, OPENGOVREPORT.OCF.TW. We hope that the report served as an open platform for participation so that the conversation will continue long into the future.

Note

Criticism can be found in the following reports: “Public Hearing on the Forward-looking Program Was Not Open to the Public, Is This Open Government?”(Chang 2017) & “Infrastructure Development Program Proved Open Government an Empty Promise” (CK 2017) ↩︎

1. Laws, Regulations, and Policies

Key Findings

No dedicated law on open government and open data in Taiwan

There is no dedicated law on open government and open data in Taiwan. Promotion mostly relies on executive orders. Except for the Administrative Procedure Law, citizen participation process and deliberative participation is not yet institutionalized.

Taiwan Government started a series of policy making on open data in 2012

In the early days, the Administrative Procedure Law and the Freedom of Government Information Law were the key laws stipulating that government information should be made public. In 2012, thanks to the call for open government worldwide and for transparent governance in Taiwan, the government started to put many efforts into formulating policies and executive orders related to open government.

Open data is mainly driven by the Executive Yuan and supported by the advisory teams composed of agencies and civil society representatives. However, this structure does not work well as expected

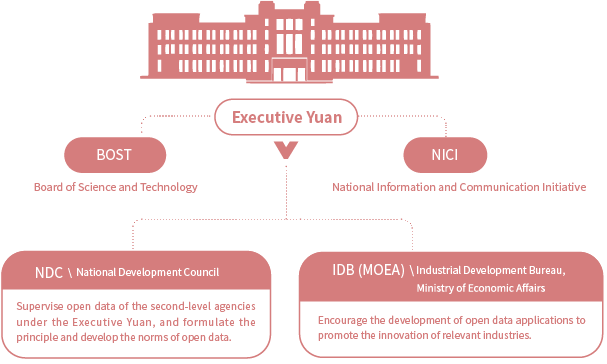

In Taiwan, open government and open data policies were mainly driven by the Executive Yuan with the Board of Science and Technology (BOST) and the National Information and Communications Initiative Committee (NICI) as its staff organizations. All second-level agencies under the Executive Yuan have an open data advisory team. However, due to the lack of knowledge in open data among administrative agencies, the above structure does not work as expected.

The Taiwanese government lacks high-level planning when it comes to open government. The result of open data policy highly relies on the political will of political appointees

The government does not have a clear blueprint of open government and how it works in current governmental structure. That is why the government has made many political valuable promises yet lack concrete strategic planning for the framework, political culture, and legislation.

1-1. Laws, Regulations, and Policies on Open Data and Open Government in Taiwan

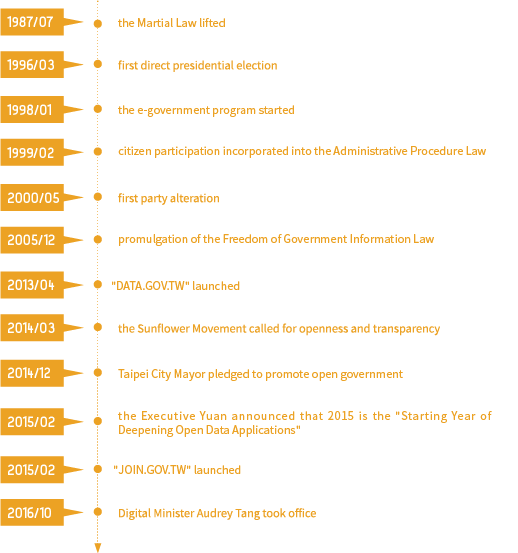

Legislative History of Relevant Laws and Regulations

The realization of open data and open government relies on the support of a healthy legal environment. In Taiwan, the legislation began rather early. The government started promoting e-government as early as 1989. Although the focus was on improving government efficiency, the use of digital data was already an important topic. In the 1999 Administrative Procedure Law, there were early-stage guidelines for making government information public but with the purpose of protecting civil rights.

The 2005 Freedom of Government Information Law (referred hereafter as the Information Law) is the first law in Taiwan stipulating that government information should be made public. Its purpose is very clear: “This Law is enacted to establish the institution for the publication of government information, facilitate people to share and fairly utilize government information, protect people’s right to know, further people’s understanding, trust and oversight of public affairs, and encourage citizen participation in democracy.”

The Information Law also clearly defines that government information should be made public, and that all information shall be actively made available to the public unless otherwise specified as being exempt. Such information to be made public includes regulations and orders, structures and communication of government agencies, administrative guidance, administrative plans, budgets and audits, results of petitions, decisions of administrative appeals, documents related to public works and procurements, subsidies, and meeting records of agencies based on a collegiate system.

However, even though the Information Law does require the government to make information public in an “active and timely” manner, it does not clearly define what “timely” is or specify the form and channel through which the information should be made public. The scope of the Law is confined to safeguarding “people’s right to know” and does not touch upon the aspects relevant to information application (Zhu & Zeng, 2016).

Across the globe, as technology and democratization movements advance, people’s demand for transparent and open government grows. In 2008, the US Federal Government took the first initiative to open government data on a large scale. When Barack Obama became the US President in 2009, he immediately signed a memorandum on “Transparency and Open Government”. The memorandum stressed that government should be a system of “transparency, public participation, and collaboration”. By 2011, open government became an unstoppable movement worldwide and the Open Government Partnership (OGP) was established. The OGP now has 75 member countries that work together to open government data and achieve transparent governance.

This trend also influenced how the Taiwanese Government viewed open government data. In this period, Taiwanese society began to call for a more transparent government and government accountability. The 2014 Sunflower Movement is a good example of people’s distrust of the government due to a lack of public information and accountability in decision-making on the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement with China.

The global wave of open government and changes in Taiwan’s political environment drove the government to consider the importance of open data and open government. In 2011, Minister without Portfolio Cyrus Chu tried to implement open data yet the departments still lacked motivation and consensus. In 2012, Minister without Portfolio Simon Chang (who later became the Premier of the Executive Yuan in 2016) also strongly supported open data. At the same time, open data and civic tech communities began advocating the idea from outside the government. The communities engaged in in-depth communication with and gave consultation to government agencies and acted as the bridge between the government and citizens. More importantly, they collaborated with the government to develop open data formats and licenses. This public-private collaboration accelerated open data in Taiwan.

In October 2013, the “Strategy to Promote Open Government Data” was discussed in the 31st NICI meeting [1]. A month later, at the the 3322nd Executive Yuan Meeting, the Executive Yuan (a Yuan is a first-level government agency in Taiwan) took the initiative to plan for open government data (Lee, Lin, & Chuang, 2014). The “Resolution of the 3322nd Executive Yuan Meeting” became critical to later open data legislation and affected many relevant laws and regulations, including the 2014 “Open Government Data Operating Principle for Agencies of the Executive Yuan” (referred to hereafter as the Operating Principle) and the “Essential Requirements for Open Government Datasets”. Under this policy, the National Development Council (NDC) established the open government data platform, DATA.GOV.TW, to supervise open data in second-level agencies.

The ide@Taiwan 2020 Policy White Paper published in 2015 reveals that the government attaches great importance to open data and citizen participation. Also, it looks into and plans for deregulation on advancements of the digital era, such as the sharing economy, virtual currency, cross-border online transaction tax, online petitioning and voting, digital assets and legacy, and copyright laws and regulations amendments. The “Fifth Stage E-Government” project launched in 2016 is data driven, people-centric, and relies heavily on public-private collaboration. The purpose is to “gather and analyze people’s needs through big data, improve government transparency and public information through open data, and provide more comprehensive services that meet people’s needs through personal data (my data).”

After the advocacy and collaboration of open data and tech communities, the NDC under the Executive Yuan published the “Open Data License Terms” to replace relevant terms in the “Essential Requirements for Open Government Datasets”. This license covers all data on DATA.GOV.TW and is in accordance with internationally accepted Creative Commons (CC) licenses. It ensures that copyright will not be reclaimed, no utilization is limited, and sublicense is allowed.

Currently, guidelines for open data and open government in Taiwan mostly come in the form of executive orders instead of laws and regulations that went through the legislative process. Therefore, current open data guidelines have some limitations and only apply to agencies under the Executive Yuan. There are also no detailed guidelines regarding the open data formats. Therefore, some members of open data communities support a separate open data act and the Ministry of Justice also attempted to amend the Information Law to manifest the spirit of open data. However, due to lack of consensus on open data between all stakeholders, the amendment never came through.

Up to today, government and society have still not reached an agreement on how open data should be included in laws and regulations. Those who are opposed to a separate act say that Taiwan’s government structure is different from that of other countries and that legislation takes more time in Taiwan. Therefore, insisting on passing a separate act first may actually slow down open data while executive orders provide speed and flexibility. Supporters of a separate act argue that this legal basis should be part of the foundation of a more open and transparent government. The current legal basis consists of the Information Law and the Operating Principle. The former, on the one hand, requires government information to be made “public”, but not “public online” (only needs to be published in the Government Gazette). Even if the information is made public online, the Law says nothing about data format and licensing. Therefore, the Law in itself is not enough to truly promote open data. The Operating Principle, on the other hand, only applies to agencies and units under the Executive Yuan and not to the other four Yuan’s [2] of the government.

Legislative History of Citizen Participation and Collaboration

While there have been relatively specified laws, regulations, and policies on open data in the past three years, there has been none on “citizen participation”, another key element of open government. Since citizen participation is more of a principle and there are multiple operating models, the concept is incorporated into various administrative procedures. Some existing administrative procedures have already included citizen participation processes, but deliberative participation is not yet institutionalized.

The 1999 Administrative Procedure Law was the first law to clearly stipulate that people should have the opportunity to participate in administrative dispositions, regulations and orders, or administrative plans and express their opinions. Based on its purpose, the Law has promoted citizen participation in five aspects, which are transparency, participation, debate, generalization, and partnership. Transparency: opening the decision-making process to the people, enhancing accountability and monitoring mechanisms. Participation: embracing citizen participation in administrative decision making. Debate: replacing one-sided decision making with debates. Generalization: administrative procedures turned from case-by-case dispositions into a generalized institution. Partnership: administrative agencies working with parties intervening into administrative procedures (Yeh & Kuo, 1999).

| Aspects | Implication | In the Law |

| Transparency | opening decision-making process to the people, enhancing accountability and supervising mechanisms | making information public, opening documents of contact for a purpose other than that of administrative procedure, publishing information of administrative contracts, promulgating legal orders, releasing administrative rules published in the Government Gazette |

| Citizen Participation | embracing citizen participation in administrative decision making | inviting relevant parties to make a statement, promulgating legal orders and allowing comments as well as petitions regarding the orders |

| Debate | replacing one-sided decision making with debates | holding hearings, regulating the provisions incidental and effect of administrative disposition, and holding hearings on legal orders and finalizing decisions on administrative plans |

| Generalization | administrative procedures turned from case-by-case dispositions into a generalized institution | legal orders and administrative rules |

| Partnership | administrative agencies working with parties intervening into administrative procedures | involving the parties in incidental provisions of administrative dispositions, administrative contracts, and administrative guidance |

Table 1.1 Five Aspects of Citizen Participation the Administrative Procedure Law Promotes

The 1994 Environmental Impact Assessment Act is another piece of legislation incorporating citizen participation. This Act stipulates that an environmental impact assessment should include a stakeholder meeting, environmental impact assessment report, an on-site inspection and hold a public hearing. Although it seems that citizen participation is in every stage of environmental impact assessment according to the Act, it is not the case in practice. According to leading scholars of Taiwan’s environmental impact assessment, citizen participation is, at best, preliminary and incomplete in the process. That is because that the over-reliance on experts and science in the narrow sense renders citizen participation a mere formality (Du, 2011/2012; Fan, 2007/2008; S. R. Xu & S. F. Xu 2001, as cited from Tai & Huang, 2014). Some researchers proposed to add formal and legal binding hearings to the process while others proposed introducing deliberative democracy to draw attention to the importance of discussion (Tai & Huang, 2014).

Laws and regulations on public-private collaboration are not yet comprehensive and the private sector usually participates in the collaboration by being a member of a committee, a consultant or a contractor. Neither citizen participation nor public-private collaboration is supported by institutionalized laws and regulations.

However, the online petition website, JOIN.GOV.TW, is worth mentioning because of its stronger administrative regulation basis.

1-2. Structure of Agencies Working on Open Government in Taiwan

Current Organizational Structure

Figure 1.2 Organizational Structure

Currently, open data policy is mainly driven and implemented by the Executive Yuan. All second-level agencies under the Executive Yuan are required to set up an open government data advisory team and upload the data to DATA.GOV.TW pursuant to the Operating Principle. On the other hand, the Industrial Development Bureau (IDB) is responsible for encouraging the development of open data applications to create value-added, which includes promoting the innovation of relevant industries.

For local governments, open data is practiced based on the Information Law. However, due to a lack of comprehensive laws and regulations on “open government”, each local government has different organizational structures and operation when it comes to open data. Most local governments actually assigned their department of information technology (ex. Taipei City), department of information (ex. New Taipei City), or other departments to handle this work. Since these departments are at the same administrative level as all other departments, open data can only be realized at the local level when there is strong support from the mayor or magistrate.

All second-level agencies under the Executive Yuan have an open data advisory team which regularly conducts inspections on the progress of open data in the agency. A subordinate agency must report its open data progress to the second-level agency which it is under. An open data advisory team of a second-level agency holds 2~4 review meetings annually to look into the agency’s performance. The Executive Yuan itself holds 2 review meetings annually, announces its annual open data goals at the beginning of the year, and reviews the result at the end of the year. Second-level agencies must send information regarding their open data status to the Executive Yuan for future reference.

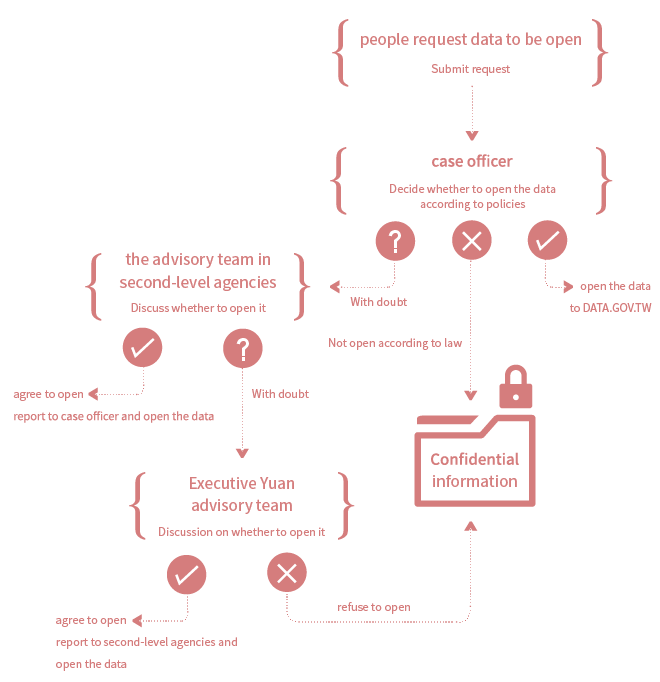

Under this two-level mechanism and the principle that “unless otherwise specified as an exception, all information shall be open”, when a citizen requests a second-level agency to open a specific dataset and the agency refuses, it must provide a reason. If the citizen is not convinced by the reason, he or she can make an appeal to the Executive Yuan and it can overthrow the original decision and request the agency to open the data.

Figure 1.3 The Process of Requesting Open Data

Challenges under Current Framework

In theory, the advisory team acts as a decision maker instead of a consultant. In reality, the team rarely performs actual decision-making. After the agency receives a person’s request to open up data, if the case officer determines that the data cannot be opened under the law or the data is incomplete, of poor quality, the request will not be sent to the team at all. In addition, since only one-third of the team members are citizens and the members have different understanding of open data, their discussion sometimes fails to respond to what civic tech communities and the society expect. Many second-level agencies choose not to open the meeting minutes of their advisory team in full, which has limited the impact of the team as well.

Also, even though second-level agencies do send their open data status to the Executive Yuan for future reference, at least in formality, the advisory team in the Executive Yuan cannot, in fact, achieve due diligence. The government does not have enough manpower to conduct a preliminary review on the content and quality of information submitted or organize the information before the meeting for the team to have a meaningful discussion. This greatly hinders the function of the advisory team. However, the meetings at the Executive Yuan-level still play a role in terms of politically showing the importance of open data because the heads of second-level agencies are gathered in the meeting to re-confirm policy directions.

Apart from the advisory teams at both levels, open data is mainly conducted by the case officer in the agency, yet many of them do not truly understand the concept of open data. There is no standard format for data that all agencies generate that can serve as a reference for the executive units, nor is there a specific process for handling people’s requests for data. Legally speaking, the case officer should follow the process of handling petitions stipulated in the Administrative Procedure Law, but many of the case officers do not think they need to do so. Therefore, the requests are not processed smoothly. Civic tech communities expect agencies to design a dedicated process to deal with open data requests.

Promoting open data requires proper legal and policy readiness yet sufficient dedicated personnel are also critical. The government did attempt to institutionalize dedicated open data coordinators within and between second-level agencies. Confined by government structure, however, the NDC is currently not able to coordinate the agencies and the case officers inside the agencies often have other tasks or inadequate authority, which has significantly limited the impact of policy implementation.

The Taiwanese government lacks high-level planning when it comes to open government. The result of open data policy highly relies on the political will of political appointees. Once the appointee is no longer in the position to support the policy, its implementation often loses steam. There is neither effort put into organizing and summarizing opinions nor mechanism for adjusting next stage policy. In terms of policy adjustment, the government fully depends on the feedback from the society and has therefore wasted much energy in meetings with various actors while little progress has been made on the overall policy.

In conslusion, perhaps the government’s real issue is that it does not have a clear blueprint of open government. That is why the government has made many political valuable promises yet lacks concrete strategic planning for the framework, political culture, and legislation.

1-3. International Comparisons

This part of the chapter discusses three international cases of how open government has been developed in the context of three different countries. In the US, the political will of politicians has been the key drive. Their tool was executive orders, and after some progress, the effort went into institutionalization and legislation. This process is the most similar to that of Taiwan. In Taiwan, however, the bureaucracy has prevented open government from making institutions or legislation. Whenever there is a transfer of power between parties, the current open government framework is very likely to face big challenges.

South Korea took the opposite direction. When the government put forward its open government policy, the legislative process began immediately and the resulting laws and regulations are rather comprehensive. In comparison, there is no separate law or act on open government or open data in Taiwan. In Europe, the European Union proposed clear policy goals on open government while each country passed laws and regulations based on local conditions accordingly. In Taiwan, there is also a policy white paper on open government, yet it neither touches upon specific operational strategies nor leads to any legislation.

| Government | Development Model |

| Taiwan | By executive orders. No separate law or act. |

| The US | By President executive orders and memorandums at first and then by the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA Act). The OPEN Government Data Act is in the legislative process now and will turn preceding executive orders into laws once passed. |

| The EU | Passed the Directive 2003/98/EC on the re-use of public sector information, focusing on the economic benefits. It was amended in 2013 and the focus was shifted toward more comprehensive aspects and goals. Member countries then internalized the goals into their national laws and regulations. |

| South Korea | Became a member of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) in 2012, started promoting Government 3.0 in 2013 and open data after passing a separate open data act. |

Table 1.4 Comparison of Open Data Development Models

The US

When open government was first introduced to the US, the concept was implemented through Presidential executive orders and President Memorandums instead of a separate act. In 2009, when President Obama took office, he immediately signed a memorandum on “Transparency and Open Government”. It stressed that the government should be a system of “transparency, participation, and collaboration”. This memorandum directed the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to issue the Open Government Directive, requesting all government agencies to open data pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act, Article 105 of the Copyright Law, and the OMB Circular A-130. In addition, the US government set up the DATA.GOV platform in 2009 (Dai & Gu, 2015).

The US’s 2014 Digital Accountability and Transparency Act serves the purpose of making government budgets and expenses transparent. In early 2016, Senator Brian Schatz sponsored the OPEN Government Data Act, which will be the legal basis for opening all government data with narrow exceptions and codifying preceding executive orders. After the Committee markup in May 2017, the Act is now cleared for the Senate. Given that it has support from both parties, it is very likely to pass (Haggerty, 2017) [3].

The EU

The EU passed Directive 2003/98/EC on the re-use of public sector information which focuses on creating economic benefits from reusing public information (Lin, 2016). In 2013, the European Commission made an amendment to the Directive and there are a few key points worth mentioning:

- The basis for pricing data reuse is changed from “Upper Ceiling for Charges” to “Marginal Costs”.

- The Directive now also applies public libraries, university libraries, and museums.

- It now specifies that the government must release information in a machine-readable format.

The amended Directive now has more comprehensive development directions and goals and member countries then internalized the goals to develop their national laws and regulations.

South Korea

South Korea became an OGP participant in 2012 and the government started to promote Government 3.0 in 2013 to change government agency culture with information technology. Also in 2013, the Promotion Availability and Use of Public Data Act was passed to safeguard citizen’s right to access information based on the principle of equality. It also specifies what data should be open and what should not.

This Act also stipulates the establishment of the “Open Data Strategy Council” to deliberate open data policy and assess the result of data inventory. Apart from that, to avoid disputes over using data, the “Open Data Medication Committee” was established to find efficient solutions.

According to the Copyright Act of South Korea, open publications of national or local government agencies can be used without licensing. The enforcement rules of the Copyright Act also stipulate the establishment of a copyright licensing system for public agencies. The South Korean Government also built the DATA.GO.KR platform after developing the Government 3.0 policy (Industrial Development Bureau, 2015).

Note

As of May 2017, the NICI was reorganized as the “Digital Nation & Innovative Economy Taskforce, Executive Yuan” (DIGI+) and the NICI Guidelines are no longer applicable. http://chuchi.cyhg.gov.tw/NewsContent.aspx?n=AFDE5898784A405A&sms=4F8F3F800B36E0EF&s=CDDF9C9CC2973F57 ↩︎

Refer to the discussion of the Information Law in the g0v community(Taiwan’s biggest civic tech community). ↩︎

http://www.rstreet.org/2017/05/18/open-government-data-act-moves-to-senate-floor-after-markup/ ↩︎

2. Open Government Data

Key Findings

Too much focus on economic development and not enough on government accountability and social justice

For the past three years, open data has been promoted for its economic benefits without an overall industry policy. Taiwan has performed relatively poorly in terms of opening data regarding government transparency and accountability and there is no open data strategy targeting the disadvantaged and promoting equality.

Quantity over quality, many key datasets were scattered across multiple websites

Government agencies have tried to open more and more data but neglected data quality. As a result, the quality of datasets is jagged and many have to be manually processed to be used. Additionally, Taiwan’s agencies release data on their websites according to the country’s Information Law, yet the data is mostly not in open formats. If the data can be further structured and integrated into DATA.GOV.TW, it will be more searchable and easier to use.

Not enough impact, policy should be driven by what citizens and civil servants need

Up to today, open data still has no significant impact on open government, citizen participation, and even the data economy. The government needs to rethink the value of open data, conduct surveys to find out the needs of potential users, and develop policy directions that make the data more “useful”. The users can include civil society organizations that monitor the government, tech communities that use the data, entrepreneurs and businesses that elevate data value, and civil servants who are both producers and users.

Civil service is short of “digital power”, system reform is much needed

Due to rigid bureaucracy, an obsolete information system, and lack of coordination between government bodies, open data has been prevented from improving administrative efficiency and even become a heavy workload for civil servants. The government needs to go beyond promises, stop giving more and more policy instructions, and conduct a comprehensive review and reform of the civil service system, which includes hiring, training, laws and regulations, and information system.

KPI driven, failed to picture what role open data should play in governance

The Taiwanese Government has worked on open data for many years and made various achievements, such as the DATA.GOV.TW website, the rising quantity of open datasets, and numerous hackathons. Yet these achievements were meant to create short-term, high performance marks that are measured by KPIs. The government does not yet have an overall plan covering key aspects of open data, including administrative procedures, digital governance, and data economy. Factors such as a lack of comprehensive legislation and policy, as well as outdated systems and personnel management mean that the success of open data initiatives rely heavily on the will of the political leader. Without implicit policy or orders from the top, open data brings little tangible change.

2-1. Introduction

Background

As “open government” became an important trend in national governance in the 21st century, “open government data” (“open data”) also became a key means of promoting digital transformation and deepening democracy. The modern state is built on the census of people and territory. As a result, national governments collect a large amount of data and information on its people. Government data is not the property of the government or of any particular politician. Data collection is paid for by people’s taxes and the data is about the people. Government agencies simply collect, preserve, and manage all the information on behalf of its people as this is their duty (Chen, Lin, & Chuang, 2013). Therefore, government data should be returned to the public domain through open licensing to demonstrate that democratic countries are open, transparent, and accountable.

The 2005 Information Law stipulates that apart from the restricted information defined (under Article 18), the government should “actively” make all government information open to the public. Opening government information can increase government transparency to a certain extent. In terms of government operation, however, the information presented in statistics provided by executive units usually only reveals the tip of the iceberg. With the rapid development of ICT, the Taiwanese Government began to open data in 2012. The ultimate goal is to release raw data in structured formats on a unified data platform and to make the data “useful” instead of simply “for display” through big data computing. Through analysis and application, open data becomes a resource that “people, companies, and organizations can use to launch new business ventures, analyze patterns and trends, make data-driven decisions, and solve complex problems” (Joel Gurin, 2014, as cited by Chu & Tseng, 2016) and data governance goals can, therefore, be reached.

Based on this idea, open data not only makes the government more transparent and accountable but also improves the quality and efficacy of government services and creates economic value. We want to stress, however, that open data is not just about economic development. It is the foundation for government transparency and citizen participation. As the government promotes open data, it should also digitalize administrative processes and build a knowledge base for sharing information, which enables citizens and the government to collaboratively build a new governance model.

| Freedom of Government Information | Open Government Data | |

| Legal Basis | the Freedom of Government Information Law (2005) | no legal basis, only administrative guidelines, the Open Government Data Operating Principle for Agencies of the Executive Yuan (2013) |

| Scope | any public data of the people or the government collected by government agencies for governance should be made public | public data should be structured and opened with a URL under an open license and in an open format |

| Purpose | making the government more open and transparent, encouraging citizen monitoring, and protecting people’s basic rights | apart from the left column, facilitating public-private collaboration and developing data economy |

Table 2.2 Freedom of Government Information vs Open Government Data

Definition of Open Data

Open data is “data that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone–subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and share-alike” (Open Data Handbook, n.d.) [1]. While conventional copyrights restrict the use, reproduction, and distribution of knowledge and data, “open” data puts emphasis on the free flow and the public nature of knowledge. This “openness” with respect to knowledge promotes a robust commons in which anyone may participate, and interoperability is maximized.

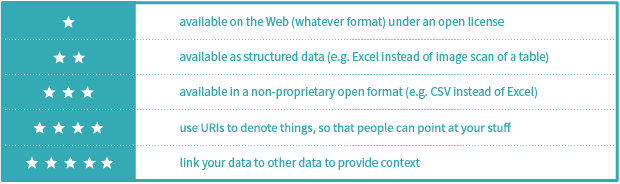

There are two internationally recognized definitions of open data, one by the Open Definition 2.1 [2] and the other by the 5-Star Open Data [3]. The Open Definition 2.1 is published by Open Knowledge International and defines that an open work must satisfy the following four requirements: open license or status, machine readable, easy access, and open format (Table 2.3).

| Open License or Status | The work must be in the public domain or provided under an open license. Any additional terms accompanying the work must not contradict the work’s public domain status or terms of the license. |

| Machine Readability | The work must be provided in a form readily processable by a computer and where the individual elements of the work can be easily accessed and modified. |

| Access | The work must be provided as a whole and at no more than a reasonable one-time reproduction cost, and should be downloadable via the Internet without charge. |

| Open Format | The work must be provided in an open format. An open format is one which places no restrictions, monetary or otherwise, upon its use and can be fully processed with at least one free/libre/open-source software tool. |

Table 2.3 The Open Definition 2.1

Compared to this relatively strict definition, Tim Berners-Lee, one of the inventors of the Web, suggested a 5-star deployment scheme for Open Data (Table 2.4) to evaluate how open a dataset is. When the two definitions are put side by side, it is easy to see that the four requirements of the former also play key roles in the latter. To get four stars or more, however, apart from the requirements, the data also needs to be connected, put on the Web, and generate more benefits in terms of application.

Table 2.4 5-Star Open Data

Research Method and Data Source

This research conducted both quantitative and qualitative analyses on the readiness, implementation, and impact of open data policies in Taiwan from 2014 to 2016. Our research method [4] is based on the third edition of Open Data Barometer (ODB), developed by the World Wide Web Foundation. The works of many open data researchers were also taken into account in the writing of this chapter.

In terms of readiness and impact, our researchers used the ODB questionnaire for survey and analysis. We, following the ODB method, also invited relevant agencies to fill out the questionnaire not only to use the answers as a reference but also to encourage the agencies to rethink open data policy directions. The draft document produced by the survey was finished in April 2017 and opened for civic tech and open data communities to review and comment from April 17th to May 7th. The researchers then took the comments and compiled the final document [5], which served as the key reference to this report.

In terms of implementation, we did not adopt the 15 dataset categories used in the ODB, instead, we applied the “20 Dataset Categories of a Data-Centric Government” [6] (Table 2.5) written and edited by “g0v” (Taiwan’s biggest civic tech community). These 20 categories touch upon important aspects of open data, including government transparency, rights of the public, the framework of economic applications, and so on. Compared to the ODB’s 15 dataset categories, these 20 types better represent the context and implementation of open data in Taiwan and are easier to conduct structured analysis on. Within each category, we picked the three to five most fundamental and significant datasets and assessed whether they met the 10 requirements in Table 2.6 to evaluate their openness. The datasets were collected, examined and reviewed by the g0v community. The list of the contributors and reviewers can be found on the github repository of this report [7]. The results of this assessment were then calculated based on the weighting of Table 2.7.

| Tier | Category |

| 0 Law and Organization | 0.1 Laws and Regulations 0.2 Government Structure and Personnel 0.3 Judiciary and Judgment |

| 1 Government Accountability | 1.1 Election and Recall 1.2 Budgets and Fiscal Balance 1.3 Civil Service Ethics and Accountability |

| 2 Government Operations | 2.1 Census Data 2.2 Basic Information of Incorporated Foundations 2.3 Procurement 2.4 National Defense and Diplomacy |

| 3 Public Safety | 3.1 Public Inspection and Violation 3.2 Crime and Incident 3.3 Environment |

| 4 Public Services | 4.1 Infrastructure 4.2 Healthcare 4.3 Basic Education |

| 5 Economic Activities | 5.1 Production and Various Licenses 5.2 Real Estate and Finance 5.3 International Trade 5.4 Labor |

Table 2.5 20 Dataset Categories of a Data-Centric Government

| Question | Weight |

| 1. Does the data exist? | 5% |

| 2. Is it available online from government in any form? | 10% |

| 3. Is the dataset provided in machine-readable formats? | 15% |

| 4. Is the machine-readable data available in bulk? | 15% |

| 5. Is the dataset available free of charge? | 15% |

| 6. Is the data openly licensed? | 15% |

| 7. Is the dataset up to date? | 10% |

| 8. Is the publication of the dataset sustainable? | 5% |

| 9. Was it easy to find information about this dataset? | 5% |

| 10. Are (linked) data URIs provided for key elements of the data? | 5% |

Table 2.6 Questions for Dataset Survey and the Weights

| Readiness 35% | Implementation 35% | Impact 30% |

| Government Policies Government Action Entrepreneurs & Business Citizens & Civil Society Each Aspect 1/4 |

Each Category 1/20 |

Political Economical Social Each Aspect 1/3 |

Table 2.7 Weightings

2-2 Readiness of Open Data

Government Policies

- No legal basis, open data has been promoted by administrative guidelines and orders

- Platform and licensing ready but data quality jagged

There is no legal basis for open data in Taiwan. There are only the 2005 Information Law and the administrative guideline, the 2013 Operating Principle, for open data operations. Due to a lack of a separate act on open data, the will and policy instruction of the political leader has been critical. The Executive Yuan appointed 2015 as the “Starting Year of Deepening Open Data Applications”, which led to a wave of open data with little regard to quality. After that, due to lack of legal and data governance basis, agencies and units that have data grew passive.

Although laws, regulations, and policies are yet to be ready, the National Development Council (NDC) setup DATA.GOV.TW in 2013 as the first open data platform in Taiwan, which was symbolic. The license terms of the platform, Open Data License Terms Edition One, were written collaboratively by the NDC and open data communities. The document was recognized by the Open Knowledge International as one of the few national license terms that are in accordance with Open Definition 2.1 [8]. After the platform was launched, datasets have grown in quantity, but there has been no systematic integration from the production ends, resulting in varied data quality. The Study of Dataset Quality Review Mechanism (UDN Digital, 2016) pointed out that on DATA.GOV.TW, 50% of data had poor machine readability, hindering data flow between agencies and value-adding data applications.

Government Action

- No data governance procedure yet, cannot improve administrative efficiency

- Executive units lack knowledge and technical training

- Local governments do open data but with a wide urban-rural gap

Currently, there is not a coordinating government agency for open data. Instead, it is the IT personnel in each agency that coordinate the executive units to open their datasets. On the one hand, the IT departments support open data but do not manage the data while the executive units lack IT skills, knowledge of open data, and practical techniques. The government offers no systematic training, so open data is yet to be integrated into the government’s decision-making process. On the other hand, before administrative procedures are completely digitalized, for civil servants in executive units, one more dataset to open means one more item to manage and update. This not only increases their workload but also drops data quality.

As for local governments, 13 out of 22 local governments have set up their own open data platforms while the other 9 use the NDC’s DATA.GOV.TW platform to open their data. Most of the local governments that do not own an open data platform are of rural areas and they tend to open much less data [9], indicating a severe urban-rural divide.

Citizens and Civil Rights

- There is the Information Law but it is very difficult to request for government information

- There is the Personal Information Protection Act but agencies tend to dodge the Act by de-identification

- The open data advisory teams do not operate in a unified manner and some meetings become mere formality

In terms of open data, citizens and civil rights, there are two issues that need attention. One, how to make sure that the government does not breach personal privacy while opening data, and two, how the government responds to civic society’s requests for data.

In Taiwan, the 2012 Personal Information Protection Act (amended in 2016) covers issues such as required consent, the right to access and correct your own data, and penalties and compensation of violation. However, when the government opens some highly controversial data, it tends to avoid the restriction of the Act by de-identification. For example, in 2015, the Taiwan Area National Freeway Bureau opened the driving routes recorded by the ETC (Electronic Toll Collection) service, the Bureau was criticized by the Taiwan Association for Human Rights (TAHR). The TAHR pointed out that though the data was de-identified, it was highly possible that it could be re-identified and therefore should not be opened [10].

As for requesting for information, the Information Law stipulates that government information shall be made available to the public actively and that within 15 days of receiving the request for government information by any person, the government agency shall determine whether to approve such a request or not. On DATA.GOV.TW, people can also make a request for data. However, it is very difficult for citizens to acquire requested data in practice. This is especially true when it comes to controversial matters, for which people often have to rely on time-consuming administrative litigation to get data despite the Information Law. For example, in 2014, the TAHR requested the Ministry of Education (MOE) to open the records of the 12-year Basic Education Advisory Meeting but was refused. The TAHR then started administrative litigation and it was not until 2016 that the MOE provided the documents requested. In addition, the government often uses the Personal Information Protection Act as an excuse not to open data. Take the Central Election Commission (CEC) for instance. The CEC originally refused to provide election bulletins in a digital and open format, saying that it involves candidates’ personal information. After advocacy from civil society, election bulletins finally became open data in the 2016 election.

Apart from laws and regulations, open data advisory teams have been set up in the Executive Yuan and all second-level agencies under it since 2015. A team consists of representatives from the agency and the society and holds several meetings in a year, covering strategic planning, data inventory, communication and promotion, and data quality. In the meeting, the team also looks into the data that people requested to make sure the agency respond to people’s needs. However, the teams are not always made up of experts and academics on open data and meet only once every few months, thus leaving the results unsatisfactory and the meeting a formality.

Entrepreneur and Business

- Too much emphasis on short-term activities and hackathons

- Lack of industrial policy for the data economy

In terms of open data, the Taiwanese Government attaches much importance to the data economy. The Industrial Development Bureau (IDB) of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA), as the coordinator of such efforts, has organized numerous competitions and hackathons in the past three years to boost the open-data-based innovative economy. The hackathons were wonderful indeed but they were short-term events that lasted only a couple of days. Without the support of an industry supply chain and a robust data economy policy, the products of hackathons were rarely developed into marketable ones. Also, open data activities driven by hackathons usually ceased after the event. All in all, there has been no comprehensive industrial policy but mostly short-term activities and competitions.

2-3 Implementation of Open Data

| Implementation 77 | |||||

| Law and Organization 61 |

Government Accountability 68 |

Government Operations 70 |

Public Safety 81 |

Public Services 90 |

Economic Activities 89 |

Table 2.8 Scores of the subcategory of implementation

Law and Organization

- Most Key Datasets Are Still not Released by Open Data Standards

Among all datasets under law and organization, we compared those released on DATA.GOV.TW and those released by the individual agency on its website. We found that the former to be relatively simple (ex. judiciary datasets) or not updated (ex. personnel datasets). Therefore, in our assessment, we chose the version released on the agency website. However, the data on agency websites is often published as public information instead of open data. For example, the Directorate-General of Personnel Administration of the Executive Yuan has extensive statistics regarding all local government agencies under the Executive Yuan, yet these statistics are not offered in an open format and contained merged cells which make machine reading very difficult. Also, the Judicial Yuan [11] has far more judiciary datasets than the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) but most of them are not machine-readable or available for batch download. In addition, the MOJ provides both Traditional Chinese and English versions of laws and regulations in XML format, but its licensing terms are not in accordance with the Open Definition 2.1.

| Law and Organization 65 | ||

| Laws and Regulations 65 |

Government Structure and Personnel 80 |

Judiciary and Judgment 39 |

Table 2.9 Scores of law and organization datasets

Government Accountability

- Need to Accelerate the Opening of Government Spending Data and Data on the Sunshine Acts Website

This type of datasets shared the same issue as the last type. Key datasets, especially those opened on the Sunshine Acts website, such as political donations, property declaration, and administrative penalties, can only be accessed through system inquiry instead of being organized into open data available for batch download. This makes the data very difficult to be read by a machine or used in technological applications by citizens. Moreover, although government budgets are already open on DATA.GOV.TW, the actual spending is still released in an annual or monthly report not easy to access or search, making it almost impossible for the people to monitor the government through the data. The Central Election Commission (CEC) does offer comparatively complete election data but the recall statistics are yet to be opened on DATA.GOV.TW.

| Government Accountability 68 | ||

| Election and Recall 83 |

Budgets and Fiscal Balance 76 |

Civil Service Ethics and Accountability 45 |

Table 2.10 Scores of government accountability

Government Operations

- National Defense and Diplomacy a Black Box, Government-Endowed Incorporated Foundations not Monitor-able

In this type of datasets, the procurement and part of the census datasets were relatively open with room for improvement in mapping and cartographic census data. As for the dataset regarding basic information of incorporated foundations, little could be found regarding government-endowed incorporated foundations despite that fact that these foundations receive huge budgets from the government and should, therefore, be monitored by the people. This means that this type of foundation can easily be manipulated by fat cats and lead to serious corruption. The national defense and diplomacy datasets were the least open ones, second only to judiciary data. Various key data, such as treaties and agreements, and results of assistant diplomacy, is scattered across government websites and offered in a non-open manner with indistinct license indication, unclear update times, and more.

| Government Operations 70 | |||

| Census Data 76 |

Basic Information of Incorporated Foundations 69 |

Procurement 94 |

National Defense and Diplomacy 41 |

Table 2.11 Scores of government operations

Public Safety

- Criminal and Environment Datasets were Relatively Open While Local Public Inspection Dataset was Barely Organized

The crime and the environment datasets were comparatively open but the public inspection dataset was scattered and fragmentary. Since public inspections are conducted by local governments, relevant datasets are scattered across local government websites. However, local governments open their data in varying degrees so the data needed to be manually processed before integrated analysis and application could be carried out. Environmental datasets were relatively open and there was real-time monitoring data of both water quality and air quality.

| Public Safety 81 | ||

| Public Inspection and Violation 67 |

Crime and Incident 90 |

Environment 85 |

Table 2.12 Scores of public safety

Public Services

- Very Open, Traffic Data Could be Ranked as 4-Start Linked Data

These types of datasets were very open, proving that open data is the foundation for better public services. In the infrastructure datasets, traffic data was the most open and could be considered as linked data. Water and electricity data was also quite open thanks to the hard work of the Ministry of the Economic Affairs (MOEA), which has encouraged public service corporations to open their data since 2016. Healthcare data was rather open, too. The Ministry of Health and Healthcare setup an open data platform [12] to provide many open datasets on medical and healthcare. As for education datasets, part of the more complete data was published on the statistics and inquiry website of the Ministry of Education (MOE) [13]. The MOE offers a lot of machine-readable data but has no license terms that indicate the data is open.

| Public Services 90 | ||

| Infrastructure 96 |

Healthcare 90 |

Basic Education 83 |

Table 2.13 Scores of public services

Economic Activities

- Relatively Open Except for Land Value

This type of datasets was highly open, which reveals that economic development takes priority in the government’s open data efforts. Multiple key datasets were already integrated on DATA.GOV.TW. Among the datasets, land value data can only be accessed through an inquiry and is offered as open data available for user download.

| Economic Activities 89 | |||

| Production and Various Licenses 86.25 |

Real Estate and Finance 82.5 |

International Trade 95 |

Labor 93 |

Table 2.14 Scores of economic activities

2-4 Impact of Open Data

Political Impact

- Transparency: has facilitated government transparency to a degree but many key datasets are not open

- Efficiency: has not improved government efficiency and implementation

Open data has had some positive impact on transparency and public accountability and this can be seen in the application of election and budget data. After Taiwan’s 2016 general elections, civic tech communities used the Central Election Commission (CEC)’s data and produced an Election Distribution Map to further analyze the results of the election. In 2015, the Taipei City Government also worked with experts in the communities and displayed the budgets of the second half of the year in an interactive and visualized way so that people could understand how the budgets would be used quickly and easily. This method was later adopted by other local governments. However, apart from elections and budgets, much key data regarding government transparency and accountability is not open or has not become 3-start data yet. For example, data about political donations, public officer property declarations, and government procurement and spending needs to be opened and organized on DATA.GOV.TW as quickly as possible to promote government transparency and public accountability.

The impact of open data on improving administrative efficiency has not been obvious. Open data did facilitate a few public-private collaborations, such as the Dengue Fever Map of Tainan City and the search system for the victims of Formosa Fun Coast explosion. These collaborations indicate that, through open data, working with crowdsourcing and civic tech communities can indeed help the government deal with emergencies. However, in terms of the overall administration system, due to differences in agency personnel, organization culture, and data format, open data has not improved cross-agency communication with tangible results. On the contrary, open data is often an additional burden for the agency. Because of complex research and evaluation procedures, conservative administrative culture, lack of knowledge and technical training, and lack of trust of government policy, open data has had very limited impact on improving government efficiency and implementation [14].

Social Impact

- The environment: open data has empowered citizens and NGOs to advocate environmental policy reform

- The disadvantaged: no tangible improvements on public services offered to disadvantaged people

Open data has empowered citizens to take active roles in public issues. Open data helps raise people’s awareness of environmental protection and is a tool that environmental protection groups use to monitor the government and enterprises. For example, local governments are working together with a maker community called Location Aware Sensor System (LASS) and the Institute of Information Science of Academia Sinica on the Airbox project. They offered handy air quality sensors to schools and the data collected is streamed to the cloud in an open format to make up for the lack of government survey stations and to provide practical education on environmental protection issues for the schools.

Moreover, in 2016, the Green Citizens’ Action Alliance (GCAA) compared the real-time monitoring data of the No. 6 Naphtha Cracker Complex and the government’s edited open data and found that more than 20,000 entries of emission that exceeded standards were missing in the latter and that only one NTD 100,000 penalty was issued, revealing the gap between the two sources of data. The GCAA then started the Transparency Footprint project [15] which attempts to promote more correct and refined open data (ex. the full list of penalized parties) to monitor the actual government action on factory pollution.

In Taiwan, open data is rarely employed to help disadvantaged people. There was still no known positive impact till the end of 2016. The Department of Social Welfare under the Taipei City Government and civic tech communities did work together and developed the Domestic Violence Map which displays de-identified domestic violence data on a map so that social workers better know which are the potential DV districts and that local neighbourhood watches can be more aware. However, scholars and social groups argued that displaying DV incidents on a map can oversimplify the issue, that it offers no tangible solution, and that it can cause the stigmatization of certain neighbourhoods.

Economic Impact

- A few new business models but no data economy industrial chain

- As the data owner, the government seizes the market and is killing the data economy

The data economy has always been an important aspect of open data to the government. For the past three years, the Industrial Development Bureau (IDB) has invested in enterprise subsidies and incentives for innovation and held product launch events. There are already a few open-data-based new business models as the result, such as the site choosing system of the Mercuies & Associates Holding and the AGRI-GIS service developed by EMCT are good examples. However, the above-mentioned cases did not facilitate the forming of a data economy industrial chain. Moreover, in the past three years, the government has worked with long-term system vendors and built websites and apps. These apps have few users, create no profit for the government, increase public servants’ workload, and are destroying many start-up business opportunities (Chen, 2016).

| Impact on | Current Situation | Problems | Possible Solutions |

| Government Efficiency | cannot improve government efficiency and implementation | complex research and evaluation procedures, conservative culture, lack of training, and lack of trust of government policy | introduce administration digitalization and increase training on knowledge, laws and regulations, and technology |

| Government Transparency | some positive impact but much more data can be open | not enough open or complete data to monitor the government | conduct an inventory check on the datasets and release the results as completely and as fast as possible |

| Environmental Issues | people’s awareness of environmental protection much preceded data-driven government reform | open data released by the government is edited | improve digital procedures and guidelines of data production to reduce human interference |

| The Disadvantaged | no tangible positive impact on the public services for the disadvantaged | lack applicable datasets | collaborate with relevant civic tech communities and think about how data can be employed to serve the people |

| Entrepreneur and Business | government incentives has led to a few new business models | no data economy industrial chain | stop developing apps and use the resources on open data infrastructure |

Table 2.15 Possible solutions to increase the impact of open data

2-5 Global Open Data Evaluations

Open data has been an important area of study in government governance and there are many global evaluation mechanisms. The Global Open Data Index (GODI) was developed by Open Knowledge International. The GODI evaluates around 100 countries annually (number of participating counties varies every year) and has conducted 4 evaluations, from 2013 to 2016. The GODI collects information regarding the status of countries’ open data from open data enthusiasts/communities, and then scores each country’s openness level based on the key datasets through crowdsourcing. The GODI’s reviewers then determine the final ranking. Taiwan became a participant in 2013 and for the past 4 years, we have moved upward in the ranking from no.36 to no.1 in 2015 and 2016. However, ranking top in the GODI does not reflect Taiwan’s open data progress but the government’s intentional efforts on improving those 15 datasets. In addition, the GODI has some limitations. First, it only focuses on the openness of datasets and cannot reveal the overall policy readiness or the following impact of open data in a country. Secondly, to provide a basis for comparison, it simplifies the politics and social context of each country, develops clear definitions for types of data to be evaluated, and chooses less than 20 datasets. This greatly limits its representativeness. Lastly, the GODI does not conduct any further research or investigation on the data and global development beyond ranking participating countries.

Another global evolution, the Open Data Barometer (ODB), adopts a methodology that is both qualitative and quantitative and produces in-depth investigation reports. The ODB was developed by the World Wide Web Foundation, also in 2013. Till 2016, there have been 115 participants in its four evaluations. However, Taiwan has never been included. This chapter already described how the ODB’s methodology was utilized in our research. Taiwan would rank about no.16 in the 4th edition of the ODB (2016). This number is merely a reference as Taiwan is not officially participating in the ODB. Still, Taiwan’s performance exhibited a distinct pattern when compared to top countries in the ODB. While most top 10 countries performed best in readiness, Taiwan performed best in implementation and performed relatively poorly in terms of impact. This shows that although the amount of open data has increased rapidly in Taiwan, we should put more focus on the infrastructure, such as policy and properly trained personnel, and interaction with data users. Attaching equal emphasis on data quality and quantity, investing enough resources and personnel training, and putting data users, citizens and public servants at the center is the best way to turn open data into a firm foundation for open government.

Data and Documents

- https://github.com/ocftw/OpenGovReport14-16/tree/master/data

- https://github.com/ocftw/OpenGovReport14-16/wiki/OGR14-16-Readiness-and-Impact

Note

See Open Data Handbook ↩︎

See 5 Star Open Data ↩︎

https://github.com/ocftw/OpenGovReport14-16/wiki/OGR14-16-Readiness-and-Impact ↩︎

See 20 Dataset Categories of a Data-Centric Government, accessed on 2017/5/15, CC BY-clkao & g0v contributors. ↩︎

Raw Data can be found here on the github page of this report ↩︎

From 2017, the Judicial Yuan has started to speed up releasing open data on DATA.GOV.TW. ↩︎

Please see “The Anonymous Notes from Civil Servants,” g0v.news, 2017/03/22., 2017/03/22. ↩︎

3. Citizen Participation

Key Findings

Citizen participation has taken root in Taiwan and the goal has been to lower the threshold to broaden participation

Citizen participation models built on deliberative democracy and open government have emerged. They mostly employ online tools and are designed to lower the threshold of participation through less rigorous forms of discussion. They are distinct from conventional forms of citizen participation (such as public hearings) and from deliberative democracy in the narrow sense which is small in scale and with strict forms.

The political will of political leaders plays a critical role in citizen participation

Realization of citizen participation relies on the political will of politicians. The success of promoting participation lies in horizontal connections and the willingness of leaders to be integrated into this process, which then pushes the agencies and departments within the bureaucracy to get involved.

The stage of policy making at which citizen participation is introduced directly affects its significance

The stage of policy making at which citizen participation is introduced has a decisive influence on the impact of participation. In addition, agenda setting, choice of issues, and the initiatives all play important roles. The method and process of participation also determine the quality of participation.

Citizen participation is still largely experimental while some models are being institutionalized

Most cases of citizen participation in this chapter were experimental. A few were implemented through administrative orders and some are being normalized or institutionalized, such as participatory budgeting at the local level.

To improve the quality of participation, it is important to train civil servants in deliberative skills and invite intermediaries to help simplify the language and connect different parties

Currently, empowering and training civil servants is the most urgent task. It is also important to invite intermediaries to help simplify the language used during discussion in order to lower the threshold of participation. These intermediaries can also help inform citizens, and at the same time, guarantee quality discussion.

3-1. Development of Citizen Participation in Taiwan

Existing Participation Models

Citizen participation as a civil right is a crucial part of democracy. In Taiwan, citizen participation is safeguarded by article 17 of the Constitution of the Republic of China (Taiwan). However, when Taiwan was under the Martial Law (1949-1987), participating in politics or expressing opinions on public issues were prohibited. When the Order of Martial Law was lifted, there was a wave of democratization movements and citizen participation finally started to pick up.

The 1999 Administrative Procedure Law stipulates that people should have the opportunity to participate in administrative dispositions, regulations, orders, and administrative plans and express their opinions. Other pieces of legislation that address citizen participation are the 1994 Environmental Impact Assessment Act and the Act for Promotion of Private Participation in Infrastructure Projects. Both Acts require evaluation committees of relevant affairs to include citizens. Apart from the above two Acts, there are other institutionalized forms of citizen participation. Public hearings and explanatory meetings are good examples but since there is no law forcing the government to accept or consider people’s input, citizens’ voices may be easily disregarded.

The Seeds of Open Citizen Participation

Since the beginning of the 21st century, democracies have met massive challenges around the world. Many so-called democratic governments merely keep the appearance of democracy with elections but have taken despotic actions that jeopardize human rights and democratic values (The Economist, 2014). People feel frustrated, disappointed, and unsatisfied by the performance of democracy (Lin, 2016) and initiated one street demonstration after another. The 2014 Sunflower Movement in Taiwan is an example of the people standing up to oppose a malfunctioning representative democracy.

In the face of weakening representative democracy, deliberative democracy became a highly anticipated possibility in Taiwan. It started during the second-generation National Health Insurance (2nd-gen NHI) reform process, in 2001. The reform was a three-year project. The Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) invited scholars to establish a citizen participation team in its planning committee. The scholars brought consensus conferences and the idea of deliberative democracy into the reform. In 2003, some Taiwanese scholars visited the Danish Board of Technology (DBT). They brought back various practices of deliberative democracy (Chen, 2012) and began to experiment on consensus conferences and scenario workshops after 2004.

CONSENSUS CONFERENCE

Volunteers are selected from different backgrounds and take relevant classes before the conference. In the conference, volunteers consult invited experts about the issue at hand. Then, the volunteers start a discussion which leads to a final report. This process usually takes 5 days.

In the 2014 Sunflower Movement, participants occupied the legislative chamber for 24 days, during which the idea of “D-Street” (citizen deliberation on the street) was created. D-Street was proposed to balance the representative power among different parties participating in the Movement. The occupation was divided into groups of protesters “inside” and “outside” the legislative chamber. While the protesters inside won more attentions from the public and the media, protesters outside the chamber felt disregarded and alienated. To expand participation, and give those outside a chance to express their views, and eventually, form a consensus, protesters began to practice D-Street (Shi, 2014). The 10-day D-Street experiment was carried out simultaneously in various locations at the demonstration site, with over 100 participants per day. Although the power relations inside and outside the legislative chamber did not truly “flip,” the practice drew public attention to deliberative democracy and the seeds of citizen participation were planted in civil society.

After the Movement, the energy of Taiwan’s civil society became very strong, the strongest in decades. In that same year (2014), Ko Wen-je ran for Taipei City Mayor with the slogan of “open government, citizen participation” and won by a landslide. His promise was later realized in the forms of participatory budgeting projects and through “i-Voting” (an online voting system).

The above events made citizen participation not only known to the public but popular among local governments. Starting in 2014, there have been experiments with less rigid forms of citizen participation (such as the “World Café”) to expand participation and lower costs. Also, with the advance of technology, online tools have become an important part of citizen participation.

This chapter explores several new models of citizen participation that were influenced by deliberative democracy and open government. These models involved online tools, and were designed to lower the threshold of participation through less rigorous forms of discussion. Such models are distinct from institutionalized channels of citizen participation and from rigid practices of deliberative democracy, like the consensus conference. Through examining various cases, we want to ask whether these efforts have successfully empowered citizens and influenced policies, and whether they were true citizen participation.

Structure of Analysis

This chapter includes the analysis of six cases of citizen participation between 2014 and 2016. It examines how citizen participation was practiced in each case, and how “open” each practice was. These cases were analyzed in an attempt to take a closer look at the participation experiences and to demonstrate different types of participation experiments between 2014 and 2016.

Our first case, the “Grassroots Forums of Civic Constitutional Convention” during the 2014 Sunflower Movement, is significant because of its bottom-up approach and its impacts on the following cases. We will then turn to two practices initiated by the government—the “Youth World Café” and the “Feiyan New Village” cases. The comparison of these two cases shows how agenda setting plays a key role in facilitating citizen participation. The next two cases are experiments on digital platforms. They are the electronic voting system in Taipei City, i-Voting, and the first online policy participation platform in Taiwan, JOIN.GOV.TW. Last but not least, participatory budgeting (PB) has become popular in many cities in Taiwan. Local governments have adopted various strategies and procedures to practice PB, so a handful of cases were chosen to represent different types of PB in Taiwan.

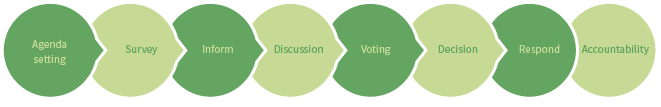

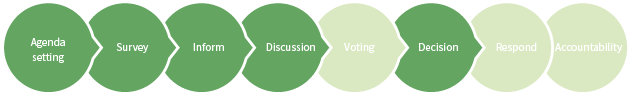

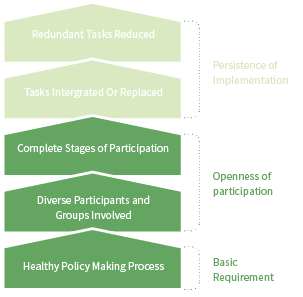

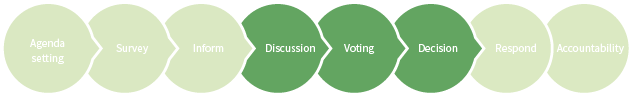

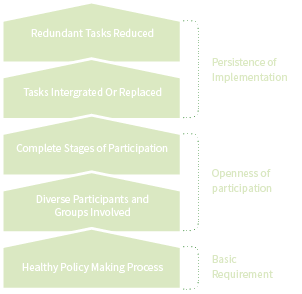

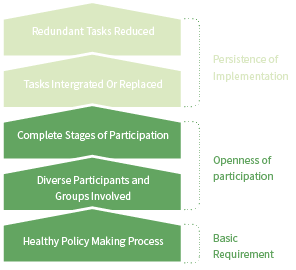

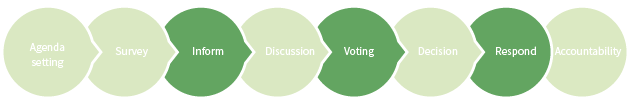

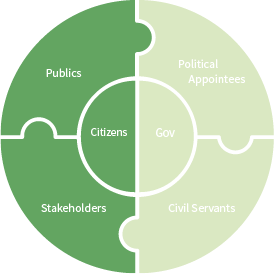

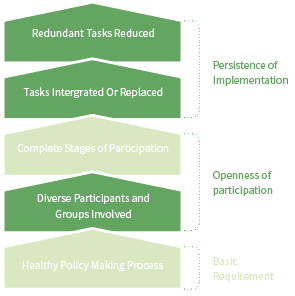

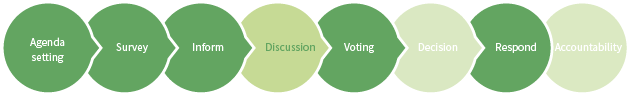

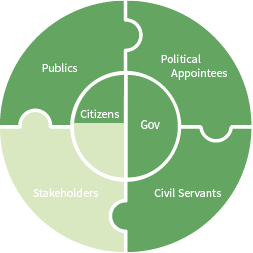

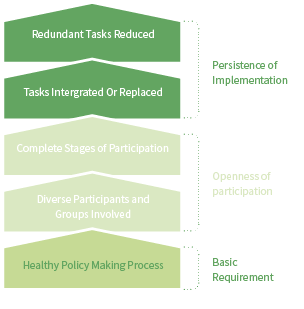

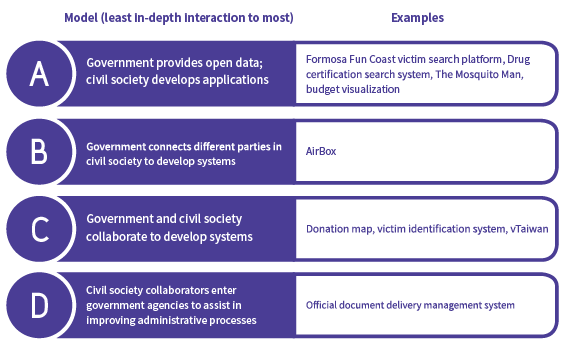

The Blulu Metrics